The second alleged culprit is ethnicity. But, as

David Lammy,

Tottenham’s MP, has said, these are no race riots. The Eighties

uprisings at Broadwater Farm, as in Toxteth and Brixton, were

products, in part, of a poisonous racism absent in today’s Tottenham,

where the Chinese grocery, the Turkish store and the African

hairdresser’s sit side by side.

So blame unemployment and the

cuts. It is true that Tottenham is among London’s poorest boroughs,

with 10,000 people claiming jobseeker’s allowance and 54 applicants

chasing every registered job vacancy. In other affected boroughs,

such as Hackney, youth clubs are closing. Unwise as such pruning may

be, it would be facile to suggest that homes and businesses have been

laid waste for want of ping-pong tournaments and skateboard parks.

The

real causes are more insidious. It is no coincidence that the worst

violence London has seen in many decades takes place against the

backdrop of a global economy poised for freefall. The causes of

recession set out by

J K Galbraith in his book, The

Great Crash

1929, were as follows: bad income distribution, a business sector

engaged in “corporate larceny”, a weak banking structure and an

import/export imbalance.

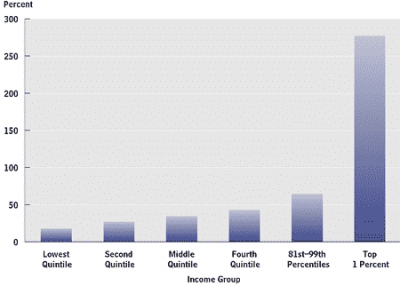

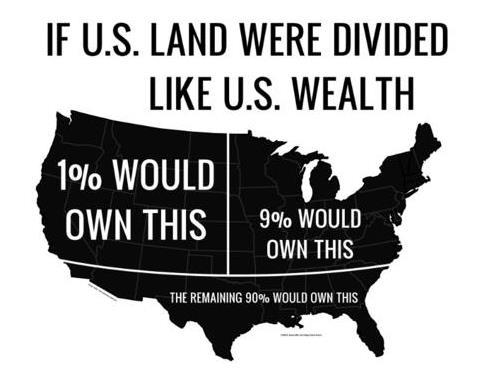

All those factors are again in play. In

the bubble of the 1920s, the top 5 per cent of earners creamed off

one-third of personal income. Today, Britain is less equal, in wages,

wealth and life chances, than at any time since then. Last year

alone, the combined fortunes of the 1,000 richest people in Britain

rose by 30 per cent to £333.5 billion.

Europe’s leaders, our own

Prime Minister and Chancellor included, were parked on sun-loungers

as London burned. Although the epicentre of the immediate economic

crisis is the eurozone, successive British governments have colluded

in incubating the poverty, the inequality and the inhumanity now

exacerbated by financial turmoil.

Britain’s lack of growth is not an economic debating point or a stick with which to beat

George Osborne,

any more than our deskilled, demotivated, under-educated

non-workforce is simply a blot on the national balance sheet. Watch

the juvenile wrecking crews on the city streets and weep for all our

futures. The “lost generation” is mustering for war.

This is not

a cri de coeur for the failed and failing. Nor is it a lament for

the impoverished. Mob violence, despicable and inexcusable, must always

be condemned. But those terrorising and trashing London are also a

symptom of a wider malaise. In uneasy societies, people power –

whether offered or stolen – can be toxic. Most of the 53 per cent of

e‑democrats calling to have the death penalty reinstated (of whom 8

per cent would opt for firing squad or gas chamber) would never dream

of torching a police car, but their impulses hardly cohere either

with

David Cameron’s utopian ambitions.

What

price for the Big Society as Tottenham, the most solid of communities,

lies in ruins? The notion that small-state Britain can be run along

the lines of Ambridge parish council by good-hearted, if

under-funded, volunteers has never seemed more doubtful. Nor can

Ed Miliband

take much credit for his unvaried focus on the “squeezed middle”,

rather than on a vote-losing underclass that politicians ignore at

their peril, and at ours.

London’s riots are not the Tupperware

troubles of Greece or Spain, where the middle classes lash out

against their day of reckoning. They are the proof that a section of

young Britain – the stabbers, shooters, looters, chancers and their

frightened acolytes – has fallen off the cliff-edge of a crumbling

nation.

The failure of the markets goes hand in hand with human

blight. Meanwhile, the view is gaining ground that social democracy,

with its safety nets, its costly education and health care for all,

is unsustainable in the bleak times ahead. The reality is that it is

the only solution. After the Great Crash, Britain recalibrated, for a

time. Income differentials fell, the welfare state was born and

skills and growth increased.

That exact model is not replicable,

but nor, as Adam Smith recognised, can a well-ordered society ever

develop when a sizeable number of its members are miserable and, as a

consequence, dangerous. This is not a gospel of determinism, for

poverty does not ordain lawlessness. Nor, however, is it sufficient

to heap contempt on the rioters as if they are a pariah caste.

One

of the most tragic aspects of London’s meltdowns is that we need this

ruined generation if Britain is ever to feel prosperous and safe

again. If there are no jobs for today’s malcontents and no means to

exploit their skills, then the UK is in graver trouble than it

thinks. Mr Osborne may congratulate himself on his prudence, but

retrenchment also bears a social cost. We are seeing just how steep

that price may be.

Financial crashes and human catastrophes are

cyclical. Each reoccurrence threatens to be graver than the last. As

Galbraith wrote, “memory is far better than the law” in protecting

against financial illusion and insanity. In an age of austerity,

there are diverse luxuries that Britain can no longer afford. Amnesia

stands high on that long list.