Parece que todos - bem, quase todos - perceberam que Portugal tem de fazer o que tem de ser feito - fora questões de detalhe (eu sei, eu sei...) e de imputação dos sacrifícios do ajustamento. Não vejo em que se poderia fazer muito de diferente no quadro do afunilamento definido pelo tempo disponível e as condicionantes em presença. Estamos prisioneiros do curtíssimo prazo. Não existem graus de liberdade significativos. O País foi, ao longo das duas últimas duas décadas, encarreirando-se para um beco muito estreito. Muitas coisas deveriam ter sido feitas ou evitadas a tempo - aí havia graus de liberdade; agora, não há. A crise internacional estreitou ainda mais o beco e tornou-o excepcionalmente perigoso. Não há alternativa; a revolução não é solução: ela não tem template; e se as coisas falham com este tipo de governação, pode tudo ir pelo cano abaixo, de modo irremediável: liberdades, direitos, níveis de vida, e, muito em particular todos, mas todos os direitos dos trabalhadores. Se uma solução radical se pode perfilar no horizonte - é possível, ainda que pouco provável (espero eu) - ela não é de esquerda.

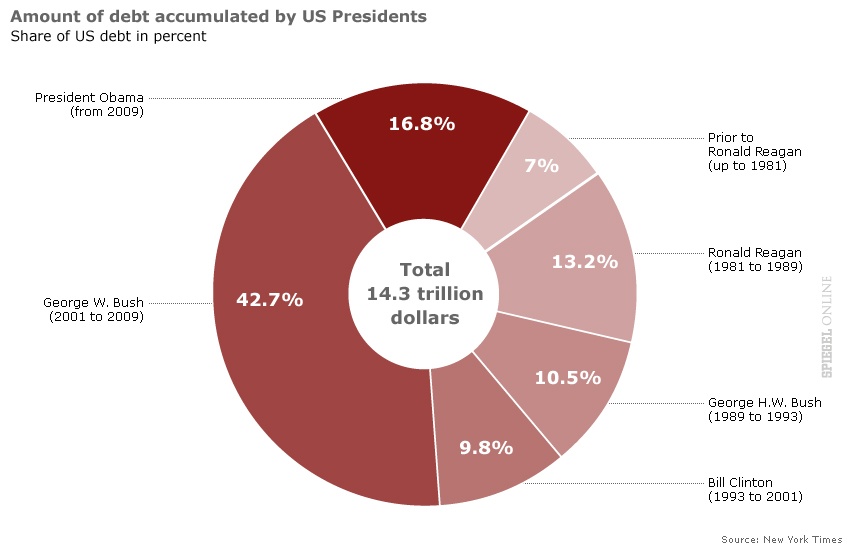

Parece que todos - bem, quase todos - perceberam que aquilo que Portugal tem de fazer é uma condição necessária de sairmos do beco, mas não, de modo algum, uma condição suficiente. Percebem que é preciso que, externamente, outros façam aquilo que têm de fazer. E também é percebido algumas dessas coisas que têm de ser feitas, como uma gestão diferente da resposta europeia, em termos técnicos e políticos. Mas o problema ultrapassa o quadro europeu e as suas discussões político-institucionais, as suas questões da governança económica e a sua gestão do problema das dívidas soberanas. O problema é, também, e principalmente, de política económica global. O texto abaixo é exemplar na arrumação das questões a esse nível - o bold é meu, e o sublinhado tem a ver, em particular, com a situação portuguesa.

Uma questão que não se percebe bem em termos europeus é a ineficiência demonstrada pelos líderes europeus: não creio que se trate só de deficiências pessoais de verticalidade e coragem política: existem outros motivos que, aí sim, poderão ser acomodados por essas deficiências. Algumas pistas (daqui) que não esgotam o assunto:

"Bringing us to the question of why it took policy makers a year and a half to get to this point. The answer is that there are strong incentives to delay. The Greek government, for which restructuring is an admission of failure, continues to hope that good news will magically turn up. Likewise, French banks holding Greek bonds cling to whatever thin reed of optimism they can and lobby furiously against restructuring. European policymakers, for their part, worry that a sovereign-debt restructuring will damage the financial system and be a black mark for their monetary union.

Centre for European Reform: Global trade imbalances threaten free trade

The developed world’s slide into recession threatens an outbreak of protectionism. Unlike in 2008, governments now have few tools with which to combat a renewed economic downturn, which raises the likelihood of it developing into a slump. If so, protectionist pressure is certain to build. The country that moves first to erect trade barriers will no doubt take the blame for the resulting damage to the trading system. But the real villains will be the countries that skew their exchange policies, tax systems and industrial structures to gain export advantage. The irony is that the countries that are most dependent on free trade – those that produce more than they consume – are the biggest obstacle to a sustained recovery in the global economy. They need to change course before it is too late: all will suffer if countries move to erect new trade barriers, but the surplus economies will suffer most.